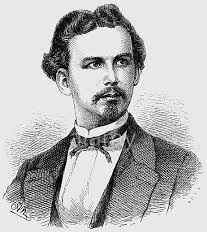

LUDWIG II e EDGAR ALLAN POE – PERSONALITA’ PARALLELE

15 02 2016Perché il re di Baviera

si riconosceva nella

personalità

del grande giornalista e

scrittore americano

Il ricordo del

giornalista Lew Vanderpoole

apparso sul “Lippincott’s

Monthly Magazine” nel 1886

dopo la morte del sovrano

(traduzione a cura di Rossana

Cerretti)

|

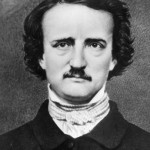

LUDWIG OF BAVARIA: a personal reminiscence The adjustment of the estates of three of my French ancestors, who died in Rouen about eight years ago, necessitated my going to Bavaria. As the three deaths, being almost simultaneous, resulted in unprecedented complications, it was manifest, from the very first, that audience must be had with the Bavarian king. So, in leaving France, I bore with me, to Ludwig, a letter of introduction from M. Gambetta, which fully explained my mission and requested the king to facilitate my endeavors as far as possible. Arriving in Munich, I sent my letter to his royal highness, expecting, of course, to be turned over to the tender mercies of some deputy, after his usual custom. To my surprise, Gambetta’s letter resulted in my being requested to wait upon the king at the royal palace the next morning at ten o’clock. Punctual to the second, I was shown into a “Is it a personal account of him?” he asked. “Did you know Poe? Of course you did not, though: you are too young. I cannot tell you how disappointed I am. Just for a moment I thought I was in the presence of someone who had actually known that most wonderful of all writers, and who could, accordingly, tell me something definite and authentic about his inner life. To me he was the greatest man ever born, -greatest in every particular. But, like many rare gems, he was fated to have his brilliancy tarnished and marred by constant clashings and chafings against common stone. How he must have suffered under the coarse, mean indignities which the world heaped on him ! And what harsh, heartless things were said of him when death had dulled the sharpness of his trenchant pen ! You will better understand my enthusiasm when I tell you that I would sacrifice my right to my royal crown to have him on earth for a single hour, if in that hour he would unbosom to me those rare and exquisite thoughts and feelings which so manifestly were the major part of his life.” “Will you be good enough to let me read, what you have written?” he asked. “I see that it is in French, the only language I know except my own.”

“I see by this that you, also, are fond of Poe,” he said, handing the proofs back to me; “and so I will tell you of a little fancy which I have cherished ever since I first began reading the works of your great fellow-American. At first, because of my respect for his genius and greatness, the lightest thought of what I am going to tell you would make my cheeks burn with shame at my presumption. After a time, I would occasionally write out my fancy, only to burn it, always, as soon as finished. Eventually I confided it to two trusted and valued friends; and now, in some unaccountably strange way, moved, perhaps, by the sympathy born of our common interest in Poe, I am going to take you into my confidence in this particular, stranger though you are. What I have to say is this : I believe, for reasons which I will give you, that there is a distinct parallel between Poe’s nature and mine. Do not be misled by assuming that I mean more than I have said. I but compared our natures: beyond that the parallel does not hold. Poe had both genius and greatness.

Injuries wound me so deeply that I cannot resent them : they crush me, and I have no doubt that in time they will destroy me. Even the laceration my heart received from indignities which I suffered as a child are still uneffaceable. A sharp or prying glance from the eyes of a stranger, even though he be only same coarse peasant, will annoy me for hours; and a newspaper criticism occasions me endless torture and misery. The impressionable part of me seems to be as sensitive as a photographer’s plate : everything with which I come in contact stamps me indelibly with its proportions. My impulses, it can be no egotism to say, are generous and kindly; yet I never, in my whole life, have done an act of charity that the recipient did not in some way make me regret it. People disappoint me; life disappoints me. I meet some man with a fine face and fine manner, and believe in the sincerity of his smile. Just as I begin to feel certain of his lasting love and fidelity, I detect him in some act of treachery, or overhear him calling me a fool, or worse.”

Arising, he began to walk slowly up and down the room. My condition is as much of a puzzle to me as it possibly can be to you. Logically, there is no reason for it. My father and mother were neither abnormally sensitive nor excessively moral. So far as I am able to ascertain, they regarded things in life very much as every one else does. It was the same, I believe, with the parents of Poe. Things he has written prove to me that he felt the same disgust for whatever demoralizes that I have always felt, only he saw how the world would behave towards him if he did not seem in sanction and approve of its rottenness. I do not blame him. His way was wisest. Deceit is best in such a case, if it can only be

I was forced to subject myself to the will of harsh, unfeeling teachers, and to the society of those who, scarcely more than animals themselves, accredited me with no instincts finer than their own. Most of the studies thrust upon me seemed dull, stupid, and worthless: because they so jarred upon me that my understanding faculties were dulled and blunted with pain, I was declared half-witted. For hours I would sit and dream beautiful day-dreams; and that won for me similar epithets. It is a misfortune to be organized as I am; yet I am what I am because a stronger will and power than mine made me so. In that lie my sole solace and comfort for having lived at all. If my reading and observation have not been in the wrong direction, much of the phenomenon which is called insanity is really over-sensitiveness. It is often hinted, and sometimes openly declared, that I am a madman. Perhaps I am; but I doubt it. Insanity may be self-hiding. An insane man may be the only person on earth who is not aware of his insanity. Of course I, for such reasons, may not be able to comprehend my own mental condition, except in an exaggerated and unnatural way. But I believe myself a rational being. That, though, may be proof of my insanity. Yet I doubt if any insane person could study and analyze himself as I have done and still do. I am simply out of tune with the majority of my race. I do not enter into man’s common pleasures, because they disgust me and would destroy me. Society hurts me, and I keep out of it. Women court me, and for my safety I avoid them. Were I a poet, I should be praised for saying these things in verse; but the gift of utterance is not mine, and so I am sneered at; scorned, and called a madman. Will God, when he summons me, adjudge me the same?”

With tearful eyes, he pressed my hand, smiled, and left the room. The learned doctors have already declared Ludwig of Bavaria insane, and kindlier judgment from those who loved him would very likely be counted wasted sympathy by the world. Lew Vanderpoole |

LUDWIG DI BAVIERA: un La sistemazione delle Con altri egli può essere sempre stato brusco, cupo, e taciturno, ma quella mattina nessuno avrebbe potuto essere più affabile e gentile di lui. Esaminò i miei documenti con l’interesse più cortese, e pesava l’intera questione con la stessa considerazione pensierosa come se fosse stato qualcosa di importanza vitale per lui. Rinunciando a diverse consuetudini bavaresi, a mio vantaggio, e avendo messo le cose in chiaro in ogni possibile direzione, era sul punto di terminare il colloquio, quando improvvisamente vide qualcosa che prolungò la mia udienza con lui per due delle più deliziose ore che siano mai state concesse dalla clemenza reale. Lasciando la Francia, come avevo fatto, un giorno prima di quanto avessi previsto, nella fretta avevo accidentalmente impacchettato con i miei documenti legali una bozza di un pezzo che avevo scritto per Le Figaro su Edgar Allan Poe. La bozza era passata inosservata tra le altre carte fino a quando l’intero pacchetto era stato aperto e sparso sul tavolo del re. Fino ad allora il suo modo di comportarsi era stato tranquillo e gentile, quasi effeminato; ma nel momento in cui vide il nome di Poe divenne pieno di entusiasmo e animazione. I suoi magnifici occhi si illuminarono, le labbra tremavano, le guance brillavano, e tutto il suo volto era raggiante e luminoso.

“Si tratta di un ricordo personale di lui?” Egli chiese. «Conosceste personalmente Poe? Naturalmente non è possibile, comunque: siete troppo giovane. Io non so dirvi quanto sono dispiaciuto da ciò. Solo per un attimo ho pensato che ero in presenza di una persona che nella realtà aveva conosciuto il più meraviglioso degli scrittori, e che avrebbe potuto, di conseguenza, dirmi qualcosa di preciso e autentico della sua vita interiore. Per me egli è stato il più grande uomo mai nato, il più grande in ogni particolare. Ma, come molte gemme rare, è stato destinato a vedere il suo splendore appannato e segnato da colpi costanti e scalfitture contro la pietra comune. Come deve aver sofferto sotto le grossolane, crudeli umiliazioni che il mondo ha riversato su di lui! e che cose dure, senza cuore si dicevano di lui quando la morte ebbe offuscato la nitidezza della sua penna tagliente! Voi potete capire meglio il mio entusiasmo quando vi dico che sacrificherei il mio diritto alla corona regale per averlo sulla terra una sola ora, se in quell’ora confidasse a me quei pensieri e sentimenti rari e raffinati, che così palesemente costituivano la maggior parte della sua vita”. “Sareste così gentile da farmi leggere, quello che avete scritto?” egli chiese. “Vedo che è in francese, l’unica lingua che conosco, oltre alla mia.” Gli porsi la bozza, e lo osservai mentre la leggeva. Appena il pezzo diventava ciarliero e pettegolo, piuttosto che critico, sembrava divertirsi.

“Vedo da questo che anche voi siete un appassionato di Poe”, disse, restituendomi la bozza “E così vi racconterò una piccola fantasia che ho vagheggiato fin da quando cominciai a leggere per la prima volta le opere del vostro grande compagno americano. In un primo momento, a causa del mio rispetto per il suo genio e la sua grandezza, il più lieve Le offese mi feriscono così profondamente che non posso restituirle: mi schiacciano, e non ho alcun dubbio che nel tempo finiranno per distruggermi. Anche le lacerazioni che mio cuore ha ricevuto da umiliazioni che ho sofferto da un bambino sono ancora incancellabili. Uno sguardo tagliente o indiscreto dagli occhi di un estraneo, anche se egli sia solo lo stesso contadino rozzo, può disturbarmi per ore; e le osservazioni critiche di un giornale causano in me una miseria e tortura senza fine. La parte impressionabile di me sembra essere sensibile come una lastra fotografica: tutto ciò con cui vengo in contatto si imprime in me in modo indelebile con le sue proporzioni. I miei impulsi, non può essere considerata immodestia dirlo, sono generosi e gentili; eppure non ho mai, in tutta la mia vita, compiuto un atto di carità del quale il destinatario non mi abbia fatto, in qualche modo pentire. Le persone mi deludono; la vita mi delude. Incontro un uomo con un viso raffinato e maniera elegante, e credo nella sincerità del suo sorriso. Appena inizio a sentirmi certo del suo amore duraturo e della sua fedeltà, lo colgo in qualche atto di tradimento, o lo sento mentre mi chiama stupido, o peggio “. Alzatosi, cominciò a camminare lentamente su e giù per la stanza. La mia condizione è come un rompicapo per me come, eventualmente, può esserlo per voi. Da un punto di vista logico, non vi è alcuna ragione per questo [mio modo di essere]. Mio padre e mia madre non erano né anormalmente sensibili né eccessivamente moralisti. Per quanto io sono in grado di accertare, essi consideravano le cose nella vita moltissimo come ogni altro fa. E’ stato lo stesso, credo, con i genitori di Poe. Le cose che ha scritto mi dimostrano che egli provava lo stesso disgusto per qualsiasi corruzione come quello che ho sempre sentito, solo che lui si rese conto di come il mondo si sarebbe comportato verso di lui, se non avesse dato l’impressione di autorizzare e approvare la sua putredine. Io non lo biasimo. Il suo modo di reagire era più saggio. La finzione è la scelta migliore in un caso del genere, se è l’unico atteggiamento possibile da assumere. Con la sua sensibilità sono state associate forza e sfida, – due caratteristiche di cui sento seriamente la mancanza. Forse, però, avrebbe potuto sopportare il mondo più facilmente di me, perché la sua infanzia fu meno terribile della mia. Durante tutta la mia infanzia sono state fatte cose, che mi hanno angosciato e ferito. Non che io sia stato trattato più duramente rispetto a come comunemente sono trattati i bambini, ma perché la mia natura era così diversa da quella dei bambini, in generale, che le cose che non li disturbavano erano offensive per me. Ho imparato presto che compagnia voleva dire dolore, e che non avrei potuto mai sapere o sentire alcun piacere a meno che io mi tenessi in disparte da tutti. Questo, per un uomo, è abbastanza difficile da fare; per un bambino è quasi impossibile. Sono stato costretto ad assoggettarmi alla volontà di duri, insensibili insegnanti, e alla compagnia di coloro che, poco più che animali essi stessi, mi ritenevano con istinti non più raffinati dei loro. La maggior parte degli studi imposti a me sembrava noioso, stupido e inutile: poiché mi mettevano in una tale agitazione che le mie facoltà di apprendimento erano offuscate e limitate dal dolore, io fui dichiarato praticamente stupido. Per ore avrei potuto sedere e immaginare bei sogni ad occhi aperti; e per questo mi sono guadagnato epiteti simili. E’ una disgrazia essere impostato come lo sono io; eppure io sono quello che sono perché una volontà e una potenza più forte di me stesso mi ha reso così. In quella illusione sta il mio unico sollievo e conforto per non aver vissuto affatto. Se la mia lettura e osservazione non sono andate nella direzione sbagliata, la maggior parte del fenomeno chiamato pazzia consiste in realtà un eccesso di sensibilità. Si è spesso accennato, e talvolta apertamente dichiarato, che io sono un pazzo. Forse lo sono; ma ne dubito. La pazzia può nascondersi a se stessa. Un uomo folle può essere l’unica persona sulla terra che non è a conoscenza della propria follia. Certo che, per tali motivi, io potrei non essere in grado di comprendere la mia condizione mentale, se non in modo esagerato e innaturale. Ma io credo di essere un individuo razionale. Questa, però, potrebbe essere la prova della mia pazzia. Eppure dubito che qualsiasi persona folle potrebbe studiare e analizzare se stesso come ho fatto e ancora faccio io. Sono semplicemente fuori sintonia con la maggior parte della mia razza. Non mi dedico ai piaceri comuni dell’uomo, perché mi disgustano e mi distruggerebbero. La società mi fa male, e io mi tengo fuori da essa. Le donne mi corteggiano, e per la mia sicurezza le evito. Se fossi un poeta, sarei lodato per il fatto di esprimere queste cose in versi; ma il dono della parola non mi appartiene, e quindi sono deriso; disprezzato, e chiamato pazzo. Dio, quando mi chiamerà, mi giudicherà nello stesso modo?” Lew Vanderpoole “ |

Categories : Senza categoria